|

|

«« go back

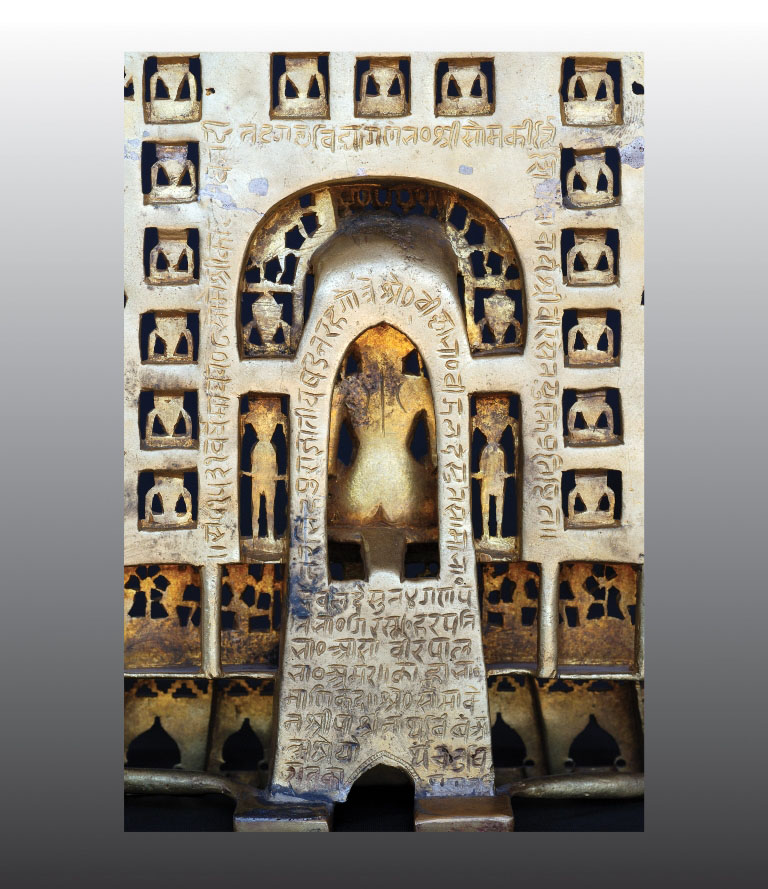

Pârshvanâtha

Gujarât, India - Brass - Height 34 cm - Dted 1475 - 15th century

This valuable image was produced within the sphere of the philosophical-religious Jain tradition led by the master Jina Mahâvîra (540-468 BC), a contemporary of Buddha Shâkyamuni (circa 563-483 AC). On a par with Buddhism, Jainism appeared during the 6th century BC as one of the great move- ments of thought and ethic directed against Brahmanism. Jainism attributes announcement of its doctrines to a group of twenty-three prophets called Tîrthamkara (“He who aids the passage to the other bank”) or Jina (“The Victorious One”), who followed one another during the Cosmic eras. However, only two have been historically ascertained: Pârshva or Pârshvanâtha, depicted here with other Tîrthamkaras, and Vardhamâna Mahâvîra, known as the Jîna.

Pârshva, the predecessor of Jina Mahâvîra, was born probably in Benares in the 9th century BC to a noble family. According to his hagiographies, at the age of thirty he left his family and gave up all his worldly goods, just as Mahâvîra did later, determined to achieve liberation from rebirth and suffering. After attaining Enlightenment, many followers gathered around him and several communities of monks and lay brothers were founded. Over the next few centuries, they joined with those founded following the preaching of Mahâvîra as they shared affinities regarding both doctrine and custom. Pârshvanâtha, who lived a long life, passed away of his own free will after long, drawn out inanition. One of the Jain traditions has it that subse- quent generations of Pârshvanâtha’s followers altered the interpretation of the teaching of the master with the pass- ing of time. This made it necessary the coming of Jina Mahâvîra, who explicitly added the vow of chastity to those which had been set down by Pârshvanâtha.

Images of Jain masters are characterized by nakedness and a clear stylistic essentiality through which the artists express one of the fundamental principles of the Jain thought, that is to say complete domination over the physical world and the ideal of perfect awareness. Pârshvanâtha is particularly recognisable by the hood of seven (in some cases five) cobra heads which stretch out above his head. The aim of this particular feature is to evoke a famous legend according to which Pârshvanâtha, absorbed in meditation, was suddenly caught up in a storm stirred up by a terrible god. Already his enemy in previous existences, the god wanted to distract

Pârshvanâtha from his meditation. Two great snake gods came to his rescue, however, joining together to protect the ascetic from the raging storm and allowing him to continue meditating undisturbed until he attained fulfilment (1).

The images depicting Jinas generally have a number of distinctive features, some of which are recognisable in this image: the throne held up by lions, the halo, a series of three parasols or umbrellas above his head, to which flabellum-bearers and heavenly musicians have been added. Identification of this image as being Pârshvanâtha is confirmed by the inscription (2) on the back, which also provides the date on and place in which it was consecrated, namely Monday 8 of the month of Mâga 1531, corresponding to Monday, 30th January 1475 of our era, in the town of Narasimhapura. The brotherhood to which the people who commissioned the image belonged, Namdîtata-gacha, is also indicated in the inscription. Division of the Jain communities into brotherhoods occurred around the mid-10th century AD, within the group of the Svetâmbaras (“White- clad”). This followed a rift which occurred between these followers and the other great Jain school of the Digambara (“Sky-clad”) (3). The poet Bhattâraka (“Master”) Somakîrti, who belonged to the Namdîtata-gacha, consecrated this image with one Âcârya Vîrasena, with whom he is mentioned in the inscription. A disciple of the great master Bhîmasena, Somakîrti was the author of three texts, two of which written in 1474 and 1476, respectively, composed in the kâvya literary style which thrived during the first half of the 7th century C. Eamongst the poets of the Indian courts. Moreover, several female names appear in the inscription, something which frequently occurs in Jain inscriptions, as wives of those belonging to the brotherhood.

Metal images such as this have been produced as votive gifts for temples, sanctuaries or family chapels particularly in north-western India.

(1) C. Pieruccini, L’Arte indiana, Corriere della Sera E-ducation.it, Milano 2009, p. 185.

(2) Many thanks to Alessandro Passi for having kindly translated the inscription from Sanskrit. (3) G. Scalabrino Borsani, La filosofia indiana, Vallardi, Milano 1976, p. 533. ALC (Free Circulation)

|